Jan 25

As the world debates the merits of just how many people this planet will realistically support and sustain, the art world continues to remind us that total population numbers are not necessarily key, but more importantly how human nature interacts with those numbers and the resources afforded and allocated among the different ethnic groups scattered around the globe.

Who would have guessed that a Spanish military operation (pre-WWII 1937) would have the impact it did on publicizing the horrors of war, and the gruesome consequences when groups of people turn to uncontrolled violence to mitigate their differences. Certainly Picasso captured the innate ability of mankind to shun their humanity and perpetuate any conceivable brutality possible, when called upon to demonstrate the strident emotionalism of conflicting political causes.

As we enter the second decade of the 21st century it is clear technology has not made the world any safer, but only made it a more efficient killing machine. We in this country bemoan nuclear proliferation and the growing number of nations capable of nuclear weaponry, while oftentimes conveniently forgetting we are the only nation to have used it militarily-actually twice. Nuclear weapons and Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) are not only stockpiled by the West and others but are also coveted by terrorist organizations around the world. The first decade has given no indication warfare will soon be a thing of the past, in fact quite the opposite, it looks to be an ongoing and escalating method for gaining political advantage, terrorizing civilian populations and an effective means for genocidal policies.

When we view the image of Guernica, the muted cries of the wounded, the faces of the dead and shattered remains of both people and animals are crowded into a landscape devoid of hope. It leaves us all in a forlorn state of despair. History is on display for all to see, yet we continue to routinely make the same mistakes over and over again.

The one glaring clue is that as mankind’s numbers have dramatically increased along with depleting the world’s resources, and the advent of technology has evolved into a false god for moral salvation, the degree of butchery has escalated in direct proportion. It is very likely we are doomed to continually finding ways of killing each other, until there is nothing left to kill.

We most likely have both the means and mean-spiritedness to make that happen.

But a 11 x 26 ft oil on canvas created over 70 years ago now, still has the power to renew our resolve if we are willing to remember its lessons. Those lessons can only be implemented if we are willing to first control our numbers so that the circumstances that create poverty, want, hopelessness and suffering can be reduced to manageable levels, so all people are able to live in a world which is more equal and sustainable.

Whether we like it or not, America is the future-as we go so goes the rest of the world. If we are not able to find the moral and spiritual determination necessary to discipline our own unfettered desires and control our own materialism, we will only lead the world farther down the path of conflict and destruction.

That will certainly continue and multiply once again the horrors represented in Guernica.

If in doubt revisit, When The Man Comes Around: Johnny Cash

Art

Jan 19

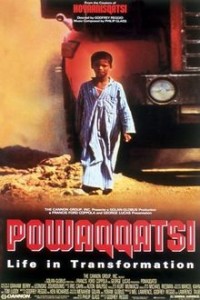

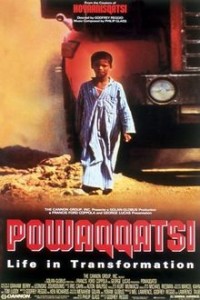

Powaqqatsi: Life In Transformation, a 1988 film written and directed by Godfrey Reggio, is the sequel to the 1983 film Koyaanisqatsi by the same director and is the second of three in the director’s trilogy.

Powaqqatsi: Life In Transformation, a 1988 film written and directed by Godfrey Reggio, is the sequel to the 1983 film Koyaanisqatsi by the same director and is the second of three in the director’s trilogy.

Although more than 20 years have passed since this film was released it loses little of its power due to the stark images that resonate in tandem with the musical score by Philip Glass. No viewer walks away from this film without at least a greater understanding of the wide discrepancies between the third world and the industrially developed countries. To live in a developed country is a stroke of immense good fortune for most of us (not all by any means). But certainly, to be able to escape the everyday poverty and grinding labor of the less fortunate on this planet is not something to be taken lightly. Reggio reminds us in every image that in many cases we are living “off the backs” of labor that is cheap and plentiful, and we seem to care little how, where or from whom our great wealth is acquired.

No where is this more apparent than in the translation of the Hopi word, Powaqqatsi, which according to the last frame in the film is not simply life in transformation, but more specifically life in transition, with its root reference to sorcery and its historical translation:

A way of life that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own way of life.

The industrialized are the “sorcerers” weaving our economic magic and imperialism over the poorer majority, cajoling them to produce and manufacture, for in many cases not even our necessities, but for luxuries that only can be described as an orgy of self-indulgent consumerism. All the while we sell a tale of free trade that is contrived as a gift to the poorest of the poor, when in reality it is nothing more than robbing the third world of their resources, while paying them a pittance to do so. If that doesn’t fit into the category of unmitigated arrogance and deception I don’t know what is.

Then what can be more haunting than the title image above? A young boy being overtaken by a mega-dump truck, roiling up from behind the monster a thick cloud of choking dust, endlessly engulfing everything within range, caring not a wit about the people disappearing into the vortex of overpowering industrialization that spews out the remains of human lives, like so much detritus.

We should care about that!

Most of us don’t though, too busy with our daily lives, seeped in our good fortune and not wanting to know how or where these gifts of privilege have come from. But thanks to people like Godfrey Reggio, we must confront the results of too much consumption, too much wealth, too much exploitation, and once we have the snapshots in our minds we are compelled to consider the plight of over one-half the population of the world. Conscience now comes into play, and even the most hardened among us are forced to consider the ramifications of both our actions and inaction.

If human nature combined with free market capitalism is irrevocably bound to over-consumption, convenience, privilege and luxury, then we can at least try to reduce our numbers so demand does not invite the economic abuses so prevalent in the world today.

Films

Jan 01

God’s Last Offer, by Ed Ayers a World Watch editor, published in 2000 would seem to be a dated piece of writing, but in the end it is still relevant today. Explaining in detail the threat of global warming, climate change and environmental degradation, Ayers uses many examples to make his point about the threats that were all around us then and which much of America was only mildly interested in at the turn of the century, and now 10 years later still struggles to find universal support.

God’s Last Offer, by Ed Ayers a World Watch editor, published in 2000 would seem to be a dated piece of writing, but in the end it is still relevant today. Explaining in detail the threat of global warming, climate change and environmental degradation, Ayers uses many examples to make his point about the threats that were all around us then and which much of America was only mildly interested in at the turn of the century, and now 10 years later still struggles to find universal support.

The title itself is an emotional indicator for Ayers that we have only so much time to remedy many of the problems he so ably describes. Dividing the threats into four categories of what he calls worldwide spikes: The Carbon Dioxide Spike – The Extinction Spike – The Consumption Spike – The Population Spike. His simple but compelling graphs outlining the profile and acceleration of these spikes are a quick study of just how much impact and change has gone in the last few hundreds of years. He then continues on to use worldwide examples to illustrate the environmental degradation and destruction that has brought us to the precipice of disaster.

This is a book that cannot be denied, but yet it still has the feel of ultimately only being read by people that already know or are already “true believers”. No one can question the author’s passion and research surrounding his many examples, but in the end many doubters will put the book down after being bombarded by statistics that tend after while to disengage the reader rather than engage. That is not necessarily a criticism of the author, but a statement of the attitudes that many will bring to books with this message seeking more information, but then giving up when any attempts at solutions seem too overwhelming.

Unfortunately many will say that after 10 years much of his examples have not come to pass but that only means that technology has staved off for a short period of time the inevitable outcomes that bode poorly for our continued survival.

My real criticism of his book is its inability to give real meaning to just how important the Population Spike is tied to the other three spikes, and the myriad of problems that emanate and dramatically escalate because of exploding population growth, particularly in the last 50 years. It is critical that all readers be reminded that all the environmental problems that exist today have been brought on by our lack of foresight in controlling mankind’s tendency to overpopulation, over-consumption and decimate that which is central to our very existence.

But in the end the author leaves us with what he believes is the last hope:

Ironically, it can be only through our acceptance of this offer – to defend our world instead of ourselves – that we have any real chance of saving ourselves and of regaining the sense of personal and family security we care about so deeply.

It would be difficult to argue against that final summary.

Books

Powaqqatsi: Life In Transformation

Powaqqatsi: Life In Transformation God’s Last Offer

God’s Last Offer